Carbon-Nature Data to Biochar Carbon Capture

Pioneering Biochar project implementation

Transparent carbon & nature Impact measurement

Clear insight reports on Carbon and Nature impacts

Creating a Biodiverse & Low-Carbon Future

Klere is a green-tech business consultancy turning investment into real-world projects.

From the set up of Biochar Operations to robust carbon and biodiversity accounting, we help you turn sustainable ideas from intent into measurable action.

Clarity from Complexity

We are driven to align business and nature with grounded solutions that make financial sense.

From clear, report-ready Carbon and Nature Analysis to frameworks that launch Energy Biochar and Carbon Capture, we work side by side with our partners to create clear, measurable paths to financially viable sustainability.

Klere Services

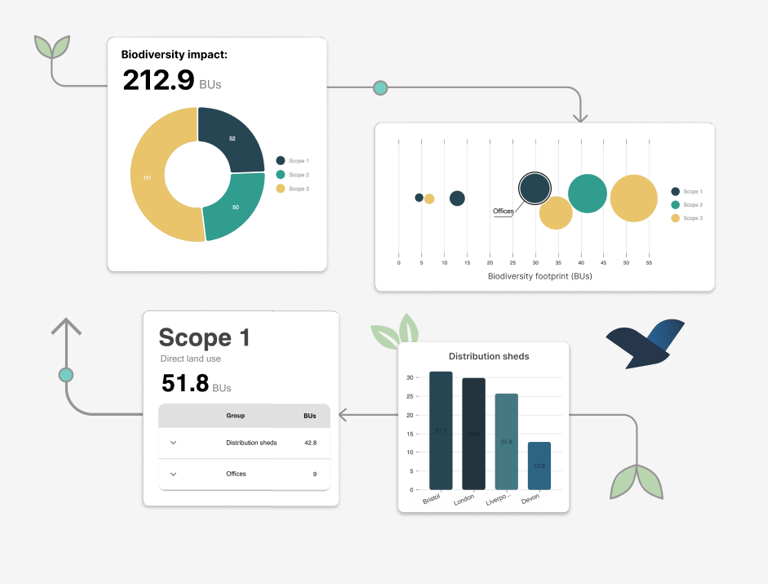

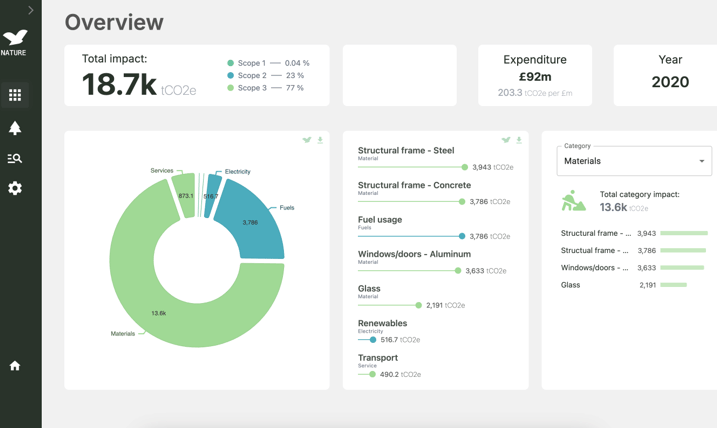

Carbon & Nature Impact Software

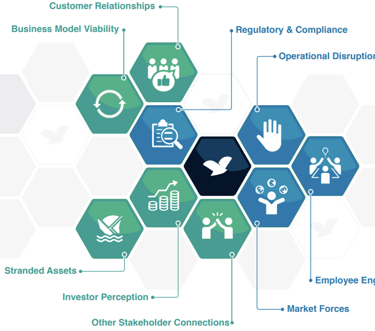

Industry validated metrics analysing carbon scope 1,2,3 as well as, nature risks and dependencies, providing a robust view on your company's impact in one clear platform.

Analysis & Reporting

Starting with financial spend, we validate & process your data—to reveal your nature & carbon impacts & risks. We screen across the business so you can set nature priorities, delivering the insight you need for strategic sustainability decisions.

A leading carbon capture technology with energy generation. Biochar as the end product has several beneficial uses & markets. We set clear paths from feasibility, business plans to project managing plant implementation. See our biochar projects.

Energy, Biochar & Carbon Capture

Here's what our clients say

"We knew biochar was a great opportunity. But we needed the skill sets & clarity of actions to launch a joint venture with our manufacturing partners. Klere stepped in early, refining our business case to secure funding approval, followed by set up & delivery of the project across multiple stakeholders. We had the right team to get our first plant online & on to the next."

Richard MacDonald, Estates Manager, Acquisitions & Disposals, Shropshire Council

"The Klere team helped us all the way from cabinet report to operational business. As Shropshire's Climate Officer, working collaboratively with their team helped put climate science into a workable business, propelling Shropshire forward with our Net Zero plan"

Dan Wrench, Climate Change taskforce, Shropshire Council

"Ultimately, it was critical to have a good business case to back the investment into Biochar production. Communication was excellent and collaborative, working alongside a team who understood Council protocol made it easier."

Stephen McDonald, Energy & Sustainability Manager, Durham County Council

Thoughts & Insights

Klere Limited

Nature data and carbon capture.

enquiries@klere.uk

Tel: 0203 583 1263

© 2024. All rights reserved.