The Klere view – taking a look at Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS).

1st February 2024

Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) has prompted considerable debate regarding its ambition and capability.

The UK government has pledged to capture and store 20-30 million tonnes of CO2 every year by 2030, equivalent to removing 4-6m cars off the road annually. This, it claims, will also create 50,000 jobs by 2030 and add £5bn to the UK economy annually by 2050.

The Climate Change Committee (CCC), the UK’s statutory government adviser, reported in its 2019 Net Zero report that CCS is ‘a necessity, not an option’ in reaching Net Zero.

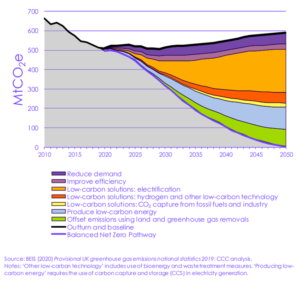

The chart shows emissions reduction categories in the CCC’s Path to Net Zero (2020). CCS (in yellow) represents some 5%.

There are the three main categories of CCS:

- Power and industrial carbon capture and storage: capturing CO2 mainly in flue gases from fossil fuel power generation and industrial processes, which is then stored deep underground or available for re-use. In the UK, this is largely sponsored by the Carbon Capture and Storage Infrastructure Fund (CIF), which provides £1 billion of capital investment for UK CCS clusters. Century, a US plant, removed 800,000 tonnes of CO2 last year, only a tenth of its capacity, indicative of the difficulties of delivering scale. 70% of the 41 CCS projects operating globally are linked to enhanced oil recovery (injecting captured CO2 into existing oil fields), a technique hardly popular with climate activists due to its environmental impacts e.g. creation of high volumes of contaminated water.

- Direct air carbon capture and storage (DACCS): fans, ideally using renewable electricity, suck in air which passes through a chemical solution or filter that captures CO2 which again is then stored underground or used commercially. Orca in Iceland, the world’s largest DACCS plant, aims to capture up to 4,000 tonnes of CO2annually, equivalent to the annual emissions of only 800 cars. Over half a billion dollars of potential investment in DAC awaits from BlackRock, the world’s biggest asset management company. All of this at a heavy cost – more investment, limited emissions mitigation, with returns yet to justify costs.

- Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), the most recent CCS technology, uses biomass e.g. plants and organic waste, to produce renewable energy, and then captures and stores the CO2 that is released, delivering ‘negative emissions’. However, only 2 million tonnes are currently captured annually by this method.

Capital costs and delays to CCS projects remain significant barriers to their progress in effectively reducing carbon emissions. More transparent regulation, greater incentives and aligned public engagement should be prioritised.

CCS has huge scalability, but results to date indicate mediocre reductions and limited ability to capture and store at meaningful scale. Results must be accelerated for CCS to become a decisive player in the path to Net Zero and limiting global warming. It is a tough ask. but CCS could be a long-term part of the jigsaw to reducing emissions, provided that significant hurdles are removed such as cost. Electrification of industrial processes, transport and the home should take precedence.